Book Ordering

For more information about ordering the book, please contact iUniverse at:

Phone - 402-323-7800

Fax - 402-323-7824

or on the web at www.iuniverse.com

All iUniverse books are distributed through Ingram Distribution and Baker & Taylor. iUniverse books can be purchased in any major bookstore, or online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or Borders.

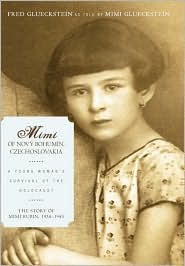

Mimi of Novy Bohumin, Czechoslovakia: A Young Woman's Survival of the Holocaust

Description

Mimi Rubin had fond memories of growing up in Novy Bohumin, Czechoslovakia, a place that ten thousand people called home. It was a tranquil town until September 1, 1939, when the German army invaded the city. From that day forward, eighteen-year old Mimi would face some of the harshest moments of her life.

This memoir follows Mimi's story-from her idyllic life in Novy Bohumin before the invasion, to being transported to a Jewish ghetto, to living in three different German concentration camps, and finally, to liberation. It tells of the heartbreaking loss of her parents, grandmother, and countless other friends and relatives. It tells of the tempered joys of being reunited with her sister and of finding love, marrying, and raising a family.

A compelling firsthand account, Mimi of Novy Bohumin, Czechoslovakia: A Young Woman's Survival of the Holocaust weaves the personal, yet horrifying, details of Mimi's experience with historical facts about this era in history. This story helps keep alive the memory of the millions of innocent men, women, and children who died in the German concentration camps during the 1930s and 1940s.

Excerpt

Chapter Two

Poland and Nazi Germany Invade Novy Bohumin in 1938 and 1939

On October 2, 1938, Polish cavalry, motorcyclists, and infantry with unfurled flags, massed at the bridge over the Olza River at Teschen, a city on the border of Poland and Czechoslovakia. The Poles carried bayonets, machine guns, and flowers. The bridge had separated the Polish and Czechoslovakian parts of Teschen since January 1919, when Czechoslovakia invaded the area that Poland claimed at the end of World War I. But now, almost twenty years later, Poland annexed Teschen and the surrounding Czech district, including the strategically positioned city of Novy Bohumin where I lived.

As I learned later, the justification for Poland's annexation of the Czech district my family lived in was the Munich Agreement. This pact was signed in the early morning hours of September 30, 1938 by Adolf Hitler, the Austrian-born dictator of Nazi Germany, Neville Chamberlain of Great Britain, Edouard Daladier of France, and Benito Mussolini of Italy. The Munich Agreement called for the Sudetenland, the western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia associated with Bohemia, to be evacuated by the Czechs in five stages. In turn, German troops would occupy the Sudetenland. In agreeing to the Munich Agreement, Adolph Hitler pledged peace and an end to territorial expansion.

Winston Churchill, a member of the English Parliament, had stood alone in his concern about Germany's increasing strength. Churchill understood what the Munich Agreement meant. On October 5, 1938, he gave a speech to the House of Commons where he stated the consequences of the Munich Agreement. "We have sustained a total and unmitigated defeat," he told his countrymen. He said all the countries of the Danube valley, one after the other, would be drawn into "the vast system of Nazi politics.' Churchill warned them. "Do not suppose that this is the end. It is only the beginning."

News of the Czech evacuation of the Sudetenland and its occupation by the Germans reached the residents of Novy Bohumin. My father followed the events closely. He read German newspapers like the Morgen-Zeitung, which he hid under the table so our Czech neighbors wouldn't see it. They frowned upon other Czechs who spoke German and read German papers. Reports reached Novy Bohumin that the Polish Army had occupied the Czech section of Teschen. Soon rumors spread that Polish troops were heading toward our town.

In the early morning hours of October 9, 1938, Polish troops entered Novy Bohumin. As a youngster, I had no understanding what the occupation of my town by Poland meant for the future. At the time, I was working in my father's jewelry store. Watching the Polish soldiers in Novy Bohumin, I saw young men wearing fatigue caps made of cloth and olive-colored uniforms with black boots. There was no outward display of machine guns or other weaponry. The Poles treated the people of Novy Bohumin politely. They liked spending money in the shops. I served the Polish soldiers who came into the jewelry store to buy my father's watches.

A month after the Polish occupation, the world's focus was on Germany and the Jews. On November 6, 1938, a seventeen year old Jew named Herschel Grynszpan, who we later learned was enraged about his family's harsh treatment and expulsion from Germany, walked into the German embassy in Paris and fired five shots at the first official who would see him.

Three days later, Ernst vom Rath, the junior diplomat shot by Grynszpan, died. Immediately, in retaliation, Nazi storm troopers and Hitler Youth rampaged through Jewish neighborhoods in Nazi Germany and Austria. From November 9-10, the terror and destruction called Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, saw more than a thousand synagogues destroyed and thousands of Jewish businesses damaged. Thirty thousand Jewish men between the ages of sixteen and sixty were arrested and sent to concentration camps such as Sachsenhausen which was less than ten miles outside of Berlin, the German capital.

Five years earlier on March 22, 1933, the SS (Schutzstaffel), Hitler's "elite guard," established the first concentration camp outside the town of Dachau, Germany for political opponents of the Nazi regime. Between 1933 and 1945, Nazi Germany established about twenty thousand camps to imprison its many millions of victims. These camps were used for a range of purposes including forced-labor, temporary way stations, and as extermination facilities built exclusively for mass murder. By 1934, the SS had taken over administration of the entire Nazi concentration camp system.

Meanwhile, news of the terror of Kristallnacht, and the treatment of the Czech Jews in the Sudetenland, reached my family and other Jews of Novy Bohumin. I could hear father telling mother that the danger was coming closer and closer. "But we will be safe," he told her, "as long as the Polish troops are here and protect Novy Bohumin from the Germans." However, the protection offered by the Poles was not to last. Within one year the Germans had replaced the Poles, and my family, as well as the other Jews of Novy Bohumin, faced the danger firsthand.

On March 15, 1939, within a year of the Germans occupation of the Sudetenland, German troops occupied Prague, the country's capital. They also took control of the western provinces of Bohemia and Moravia which they established as a German Protectorate. Seeing that Hitler had not kept his promise to end territorial expansion, both England and France issued a mutual defense guarantee to all the central European countries between Germany and the Soviet Union.

Less than six months later, at twelve noon on September 1, 1939, the German Army, entered my city of Novy Bohumin. From the window of our apartment, mother, Blanka, and I watched the soldiers marching and singing below us on Benes Street. In the hours preceding the Germans arrival, the Polish troops had evacuated the town. As father watched the soldiers leave, he knew that every male Jew in Novy Bohumin faced immediate danger with the imminent arrival of the German troops. Father had heard how Jews had been treated by the Germans after they occupied Austria in March 1938. On the first night of the German Anchluss, or annexation, the Germans looted Jewish apartments and stole valuables, pieces of furniture, and art. Austria's Jews, some one hundred eight-five thousand, were singled out for beatings and public humiliations such as scrubbing the streets of Vienna.

Father was well aware that the Nazis would soon launch an operation against the Jews in Novy Bohumin. He knew that the occupation of the Sudetenland had led to the arrest of Jews and Synagogues were torched. Thus, with only hours of the Germans expected arrival, father and other Jewish men decided that it was prudent to leave Novy Bohumin. But the families were to stay behind.

"It is a hard decision," father explained, "but Jewish women and children will be of no use to the Germans. You will be safe. The others and I will travel east into Poland away from the Germans, find work, and send for you. Is there any other choice?" he asked. On the morning of September 1, 1939, father packed a small valise with clothes, rings, watches, and other jewelry from the shop. Only the clocks on the wall, which had been for sale, remained. The familiar 'tick-tock' 'tick-tock' of the clocks was the last sounds father heard as he closed the shop for what would be the final time. I was sad to see him leave. A feeling of ill-boding gripped me. And I was right.

I never saw father again.

Unbeknownst to father and his fellow travelers on the day they left, September 1, 1939, Germany mounted an all out attack, or Blitzkrieg, on Poland. With their superior firepower, the German troops overran the western part of the country. The German Air Force, or Luftwaffe, bombed the major cities and key Polish military and civilian installations. We later learned that father's train was bombed by the Germans in an aerial attack. He was unhurt and managed to get to Krakow, one of the largest and oldest cities in Poland. Krakow is located in the southern part of Poland, on the Vistula River in a valley at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains. There he melted into the city, which was seized by fear and nervousness.

On September 3, 1939, two days after the attack on Poland, Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. The Second World War began. Meanwhile, German forces advanced across Poland. On September 6, Hitler's troops occupied Krakow, and about sixty-thousand Jews came under Nazi authority. Father was trapped.

Meanwhile, in Novy Bohumin, the Germans took over the city hall and police station using these facilities as their headquarters. There was looting by the soldiers, and father's shop was vandalized. Uneasiness fell over the Jews. The Germans used selected Jews to communicate with the other Jewish residents. One day, Blanka, my friends, and I were told to report to German headquarters, where we were registered and immediately assigned work. The Germans were interested in people capable of working. Elders like mother and grandmother were exempt. Men and boys were put to work rebuilding a bridge blown up by the Poles.

A number of young women and I were assigned to work at the Army barracks just outside the town where the German soldiers were housed. I was given housekeeping chores. Each day the others and I met at Nazi headquarters and walked, sometimes with a German guard, about forty-five minutes to the barracks. There another guard supervised our work. I scrubbed the toilets and swept the floors. And after a full day of work, I trudged back to Novy Bohumin. The situation for the Jews of Novy Bohumin soon worsened.

I saw the fire from my window. The synagogue was in flames. It was September 23, 1939 and the Jews of Novy Bohumin were observing Rosh Hashanah, or the High Holy Days. The Germans knew the special significance of Rosh Hashanah for the Jews and deliberately set fire and destroyed synagogues across Poland.

Six days later, I turned eighteen-years-old. Two months after that, on November 23, 1939, some seven weeks after Germany's invasion and occupation of western Poland, all Jews appearing in public over the age of ten were ordered to wear white armbands. The armband had to be at least four inches wide, and had to display in blue the Jewish Star of David. The Germans decreed that the armband was to be worn on the right sleeve of all inner and outer garments. Failure to wear an armband was punishable by death. The armband was another form of public humiliation. People on the streets in Novy Bohumin stared at the Jews. The Germans watched us closely, and I took every opportunity to avoid them.

Later, I was assigned to work at the hospital in the old section of Bohumin. Walking there from where I lived in Novy Bohumin brought back memories of a happier time. Before the occupation, Blanka, our friends, and I would walk to the city's old section to bathe in the swimming pool. It was a small pool called Spuckestel. It was located at the far end of town on a big piece of land. From the swimming pool I could see the Oder River. And across the river were the rolling hills of Germany.